Anatomy and Physiology

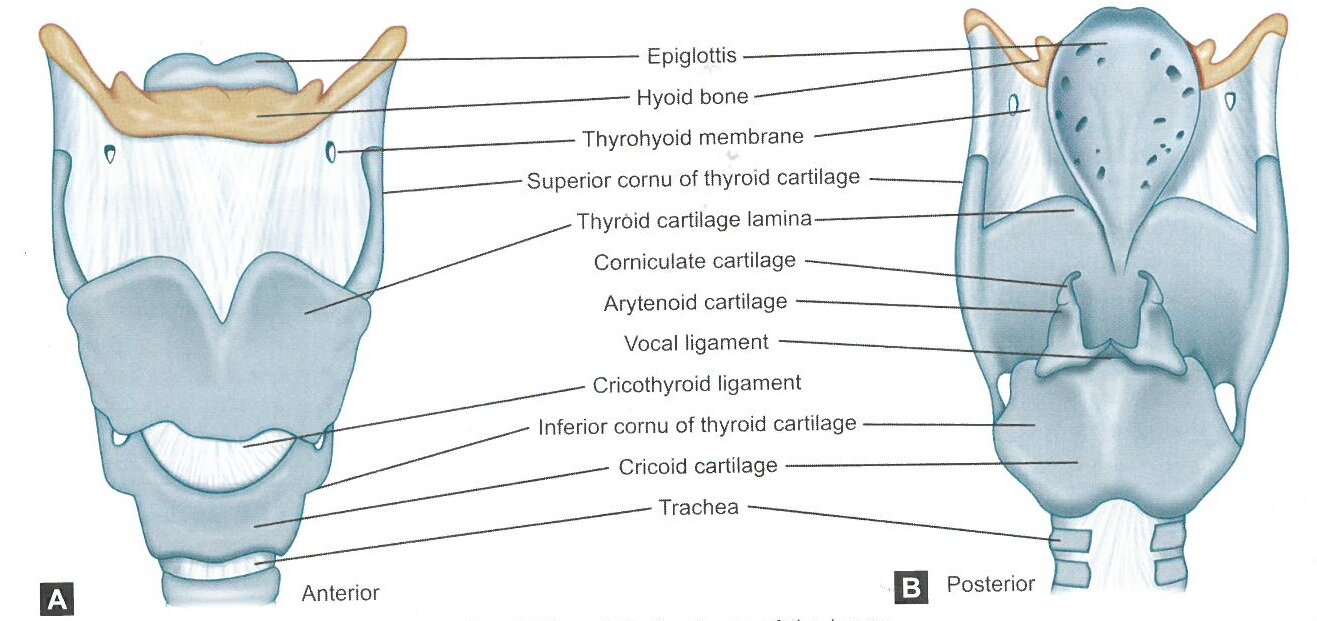

The larynx is a structure found in the neck and composed of four basic anatomic units: skeleton, intrinsic muscles, extrinsic muscles and mucosa. The most important parts of the laryngeal skeleton are the thyroid cartilage, cricoid cartilage, and two arytenoid cartilages (right).

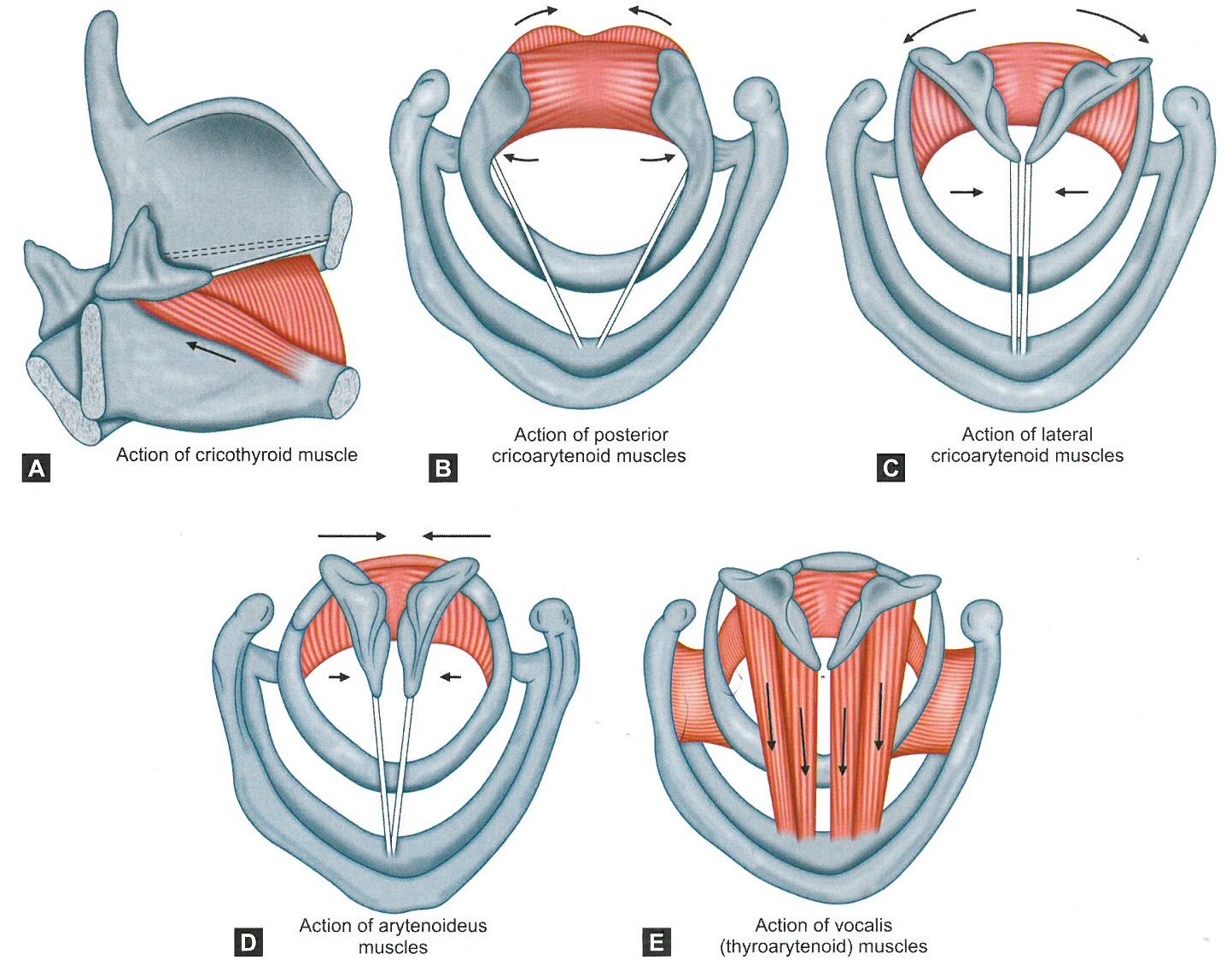

Muscles of the larynx are connected to these carilages. One of the intrinsic muscles (within the larynx), the vocalis muscle (part of the thyroarytenoid muscle), extends on each side from the arytenoid cartilage to the inside of the thyroid carilage just below and behind the “Adam’s apple,” forming the body of the vocal fold (popularly called the vocal cord) (below).

The vocal folds act as the oscillator or voice source (noise maker) of the vocal tract. The space between the vocal folds is called the glottis and is used as an anatomic reference point. The intrinsic muscles alter the position, shape and tension of the vocal folds, bringing them together (adduction), apart (abduction) or stretching them by increasing longitudinal tension. They are able to do so because the laryngeal cartilages are connected by soft attachments that allow changes in their relative angles and distances, thereby permitting alteration in the shape and tension of the tissues suspended between them.

The intrinsic muscles of the larynx. From Sataloff, R.T., Chowdhury, F., Portnoy, J., Hawkshaw, M.J., Joglekar S. Surgical Techniques in Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery: Laryngeal Surgery. New Delhi, India: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 2013 with permission.

The arytenoids are also capable of rocking, rotating and gliding, permitting complex vocal fold motion (above) and alteration in the shape of the vocal fold edge. All but one of the muscles on each side of the larynx are innervated by one of the two recurrent laryngeal nerves. Because this nerve runs a long course from the neck down into the chest and then back up to the larynx (hence, the name “recurrent”), it is easily injured by trauma, neck surgery and chest surgery, which may results in vocal fold paralysis. The remaining muscle (cricothyroid muscle) is innervated by the superior laryngeal nerve on each side which is especially susceptible to viral and traumatic injury.

Cartilages of the larynx. From Sataloff, R.T., Chowdhury, F., Portnoy, J., Hawkshaw, M.J., Joglekar S. Surgical Techniques in Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery: Laryngeal Surgery. New Delhi, India: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 2013 with permission.

It produces increases in longitudinal tension important in volume, projection and pitch control. The “false vocal folds” are located above the vocal folds and unlike the true vocal folds, do not make contact during normal speaking or singing.

Because the attachments of the laryngeal cartilages are flexible, the positions of the cartilages with respect to each other change when the laryngeal skeleton is elevated or lowered. Such changes in vertical height are controlled by the extrinsic (outside the larynx) laryngeal muscles, or strap muscles of the neck (below). When the angles and distances between cartilages change because of this accordion effect, the resting length of the intrinsic muscles is changed as a consequence. Such large adjustments in intrinsic muscle condition interfere with fine control of smooth vocal quality. This is why classically trained singers are generally taught to use their extrinsic muscles to maintain the laryngeal skeleton at a relatively constant height regardless of pitch. That is, they learn to avoid the natural tendency of the larynx to rise with ascending pitch, and fall with descending pitch, thereby enhancing unity of quality throughout the vocal range. Singing techniques may be different in selected Asian, Indian, Arabic and other musical traditions with different aesthetic values.

Actions of the intrinsic muscles. From Sataloff, R.T., Chowdhury, F., Portnoy, J., Hawkshaw, M.J., Joglekar S. Surgical Techniques in Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery: Laryngeal Surgery. New Delhi, India: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 2013 with permission.